BEIRUT (AP) — Syrians living on opposite sides of the largely frozen battle lines dividing their country are watching the accelerating normalization of ties between the government of Bashar Assad and Syria’s neighbors through starkly different lenses.

In government-held Syria, residents struggling with ballooning inflation, fuel and electricity shortages hope the rapprochement will bring more trade and investment and ease a crippling economic crisis.

Meanwhile, in the remaining opposition-held areas of the north, Syrians who once saw Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries as allies in their fight against Assad’s rule feel increasingly isolated and abandoned.

Turkey, which has been a main backer of the armed opposition to Assad, has been holding talks with Damascus for months — most recently on Tuesday, when the defense ministers of Turkey, Russia, Iran and Syria met in Moscow.

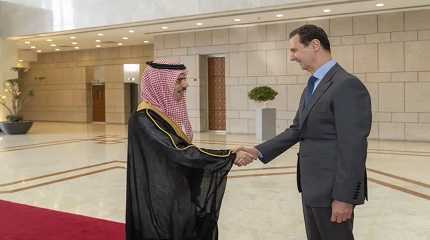

And in recent weeks, regional heavyweight Saudi Arabia — which once backed Syrian rebel groups — has done an about-face in its stance on the Assad government and is pushing its neighbors to follow suit. Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan visited Damascus last week for the first time since the kingdom cut ties with Syria more than a decade ago.

The kingdom, which will host a meeting of the Arab League next month, has been coaxing other member states to restore Syria’s membership, although some holdouts remain, chief among them Qatar. The League is a confederation of Arab administrations established to promote cooperation among its members.

A 49-year-old tailor in Damascus who gave only his nickname, Abu Shadi (“father of Shadi”) said he hopes the mending of ties between Syria and Saudi Arabia will improve the economy and kickstart reconstruction in the war-battered country.

“We’ve had enough of wars — we have suffered for 12 years,” he said. “God willing, relations will improve with not just the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia but with all the Gulf countries and the people will benefit on both sides. There will be more movement, more security and everything will be better, God willing.”

In the country’s opposition-held northwest, the rapprochement is a cause for fear. Opposition activists took to social media with an Arabic hashtag translating to “normalization with Assad is betrayal,” and hundreds turned out at protests over the past two weeks against the move by Arab states to restore relations with Assad.

Khaled Khatib, 27, a worker at a non-governmental organization in northwest Syria, said he is increasingly afraid that the government will recapture control of the remaining opposition territory.

“From the first day I participated in a peaceful demonstration until today, I am at risk of being killed or injured or kidnapped or hit by aerial bombardment,” he said. Seeing the regional warming of relations with Damascus is “very painful, shameful and frustrating to the aspirations of Syrians,” he said.

Rashid Hamzawi Mahmoud, who joined a protest in Idlib earlier this month, said the Saudi move was the latest in a string of disappointments for the Syrian opposition.

“The (U.N.) Security Council has failed us — so have the Arab countries, and human rights and Islamic groups,” he said.

Syria was ostracized by Arab governments over Assad’s brutal crackdown on protesters in a 2011 uprising that descended into civil war. However, in recent years, as Assad consolidated control over most of the country, Syria’s neighbors have begun to take steps toward rapprochement.

The overtures picked up pace since a deadly Feb. 6 earthquake in Turkey and Syria, and the Chinese-brokered reestablishment of ties between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which had backed opposing sides in the conflict.

The Saudi-Syria rapprochement is a “game changer” for Assad, said Joseph Daher, a Swiss-Syrian researcher and professor at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy.

Assad could potentially be invited to the next Arab League summit, but even if such an invitation isn’t issued for May, “it’s only a question of time now,” Daher said.

Government officials and pro-government figures in Syria say the restoration of bilateral ties is more significant in reality than a return to the Arab League.

“The League of Arab States has a symbolic role in this matter,” Tarek al-Ahmad, a member of the political bureau of the minority Syrian National Party, told The Associated Press. “It is not really the decisive role.”

George Jabbour, an academic and former diplomat in Damascus, said Syrians hope for “Saudi jobs … after the return to normal relations between Syria and Saudi Arabia.”

Before 2011, Saudi Arabia was one of Syria’s most significant trading partners, with trade between the countries reaching $1.3 billion in 2010. While economic traffic did not halt altogether with the shuttering of embassies, it dropped off precipitously.

However, even before the warming of diplomatic relations, trade had been on the uptick, particularly after the 2018 reopening of the border between Syria and Jordan, which serves as a route for goods going to and from Saudi Arabia.

The Syria Report, which tracks the country’s economy, reported that Syria-Saudi trade had increased from $92.35 million in 2017 to $396.90 million in 2021.

Jihad Yazigi, editor-in-chief of the Syria Report, said the restoration of direct flights and consular services following the current Saudi-Syrian rapprochement could bring some further increase in trade.

But Syrians who are looking to Saudi Arabia as a “provider of finance either through direct investment in the Syrian economy or through funding of various projects, especially concessionary loans for infrastructure projects,” may be disappointed, he said. Such investments will be largely off limits for now because of U.S. and European sanctions on Syria.

Even in the opposition-held areas, some greeted the normalization with a shrug.

Abdul Wahab Alaiwi, a political activist in Idlib, said he was surprised by the Saudi change in stance, but “on the ground nothing will change ... because the Arab countries have no influence inside Syria,” unlike Turkey, Russia, Iran and the U.S., all of which have forces in different parts of the country.

He added that he does not believe Damascus will be able to meet the conditions of a return to the Arab League or that Turkey and Syria would easily come to an agreement.

Mohamad Shakib al-Khaled, head of the Syrian National Democratic Movement, an opposition party, said Arab countries had never been allies to the “liberal democratic civil movements” in the Syrian uprising but threw their support behind “factions that took a radical Islamic approach.”

The Syrian government, on the other hand had “genuine allies who defended it,” he said, referring to the intervention by Russia and Iran that turned the tide of the war.

But in the end, he said, “No one defends a land except its people.”