by Harsh Mander

26 June 2019; The Wire: The fact that you could be punished in this way holds a mirror first to the craven collapse of the integrity and independence of India’s institutions of criminal justice.

Dear Sanjiv,

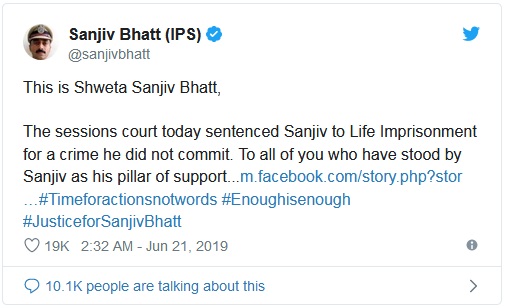

I don’t know whether you will get to read this letter, and if so when. Possibly your indomitable life partner Shweta Bhatt will carry a copy to you when she goes next to meet you in prison. But she has, at this moment, so much to fight and cope with, she may well forget the trivial matter of this letter.

If you do get this letter ultimately, I grieve as I imagine you reading it in the loneliness of your severe prison barrack somewhere in the district of Jamnagar. I have seen the inside of many prisons in India’s districts during my years in the civil service. I can therefore imagine how hard it would be for you, each day merging with the monotony of the next, sleeping maybe on a hard floor, using a smelly common toilet, with little protection from the hot summer sun, and from flies and mosquitoes.

You have already spent the last nine months in prison. But however arduous this would have been, you would still have had held on to the hope that some court – the district sessions court, or at least India’s highest courts, in Ahmedabad or Delhi – would secure justice for you.

Instead, the order of the Jamnagar district sessions court sentencing you to 30 years in prison would have come as a very hard blow. However, I know that you are a very brave and determined fighter. You will continue to fight for justice, to struggle unflaggingly to prove your innocence, to one day walk free.

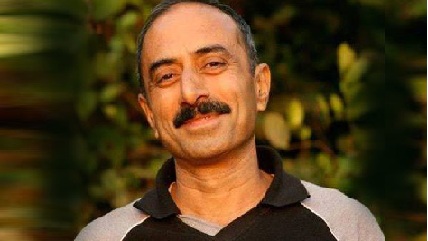

I want you to know, in your solitary moments in the isolation of your stifling and gruelling prison cell, that there are a great many people in India, and around the world, who are with you, in solidarity, as you fight your life’s hardest battle. We believe in your innocence, and know that you are being victimised only because you had the singular courage to testify against the most powerful man in the country, because you sought to establish his guilt in one of the most cruel and brutal massacres that independent India has seen, in 2002.

I want you to know, in your solitary moments in the isolation of your stifling and gruelling prison cell, that there are a great many people in India, and around the world, who are with you, in solidarity, as you fight your life’s hardest battle. We believe in your innocence, and know that you are being victimised only because you had the singular courage to testify against the most powerful man in the country, because you sought to establish his guilt in one of the most cruel and brutal massacres that independent India has seen, in 2002.

That what you are undergoing is transparently the consequences of the extreme hubris of both him and the second most powerful man in the country today, and of the brazen abuse of state power for petty revenge against a courageous and undaunted whistle-blower. I cannot recall any comparable case of a whistle-blower in India — of a senior official who dared to raise his voice against the person occupying highest office — who was punished in the way that you have been, sentenced to spend the next three decades of your life in jail.

The fact that you could be punished in this way holds a mirror first to the craven collapse of the integrity and independence of India’s institutions of criminal justice – investigating agencies, the courts and official human rights agencies. That you were let down in the end by your brothers and sisters in khaki uniform must hurt enormously, as would their silence after your life-sentence.

The absence of any significant outrage in the media reflects the extent to which it is willing to watch the open and wanton misuse of state power without indignation or protest.

The collapse of state institutions, even of constitutional bodies like the Union Public Services Commission (UPSC) have also been on disgraceful display in your case. I had written in Scroll.in about my disappointment at the pusillanimous silence of the UPSC (set up under Article 315 of the Constitution to safeguard the independence of the civil services) when in 2015 you were dismissed from service, with the concurrence of the UPSC, for the relatively minor misdemeanour of a few days of unauthorised leave of absence.

Dismissal is the gravest administrative punishment that an officer can be dealt with, reserved in the rarest of cases only for the most serious offences by public officials. Yet the UPSC passed orders dismissing you from service, without even giving you the chance to defend yourself. As I had observed then, I have known IAS officers who proceeded on unauthorised absence sometimes for years, taking employment overseas or with private companies, but most escape any punishment, let alone dismissal, for years.

Even if it is accepted that your leave was unauthorised, something that you contested, ‘a rap on the knuckles with a written warning or letter of displeasure, and leave without pay for the period of absence, would seem a reasonable and proportionate penalty for the alleged misdemeanour,’ as I had written then.

The mystery of why the highest powers of the land were so determined that you be dismissed from service is easily resolved by the way that you had used those days of ‘unauthorised leave’. You had daringly, as a serving police officer of the Gujarat cadre of the Indian Police Service, testified against the country’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, charging him with criminal complicity in mass murder.

You had done this before the Special Investigation Team of the Supreme Court, and Raju Ramachandran, the amicus curiae of the Supreme Court (and later filed this as a written statement on an affidavit to the Supreme Court). The Special Investigation Team of the Supreme Court and the amicus curiae were investigating charges by Zakia Jafri, widow of the former MP Ehsan Jafri. Ehsan Jafri was brutally killed with around 70 other people at the Gulbarg Society of Ahmedabad, in 2002. His widow Zakia Jafri had claimed that the then chief minister, Narendra Modi, was the first accused for a “deliberate and intentional failure” to protect life and property, and failure to fulfil his constitutional duty.

Your dismissal from service was as shocking as it was unprecedented. But we thought then that they had done their worst by you. We did not anticipate that much worse was to follow, and that the powers that be would not rest until their revenge was complete by ensuring that you spend the rest of your life in jail.

Your punishment is a reflection of how formidable and threatening you are as a witness in one of independent India’s most important cases of criminal command accountability for communal massacre. Of how dangerous was the evidence which you brought forth. Of how important it was to give a message not just to you but to anyone else in the country who dares to cross swords with the most powerful in the land: if this can be the fate of a senior police officer, then what can happen to an ordinary citizen?

There were other police officers who were present in the highly disputed meeting presided over by Modi late on the night of February 27, 2002. But they all claim that they do not remember being at the meeting, or that they do not remember that Modi gave the instructions which you claim he did, or that you were not even present at the meeting. But your driver and a BBC correspondent who was present with you when you set off to attend this meeting confirm that you did attend this meeting.

You knew well that your claim about what chief minister Modi had instructed senior officers to do after this meeting was utterly explosive.

You still chose to speak out. To say and do what you did called upon you to summon the highest courage. You said to the SIT and the Supreme Court that Modi had “expressed the view that the emotions were running very high amongst the Hindus and it was imperative that they be allowed to vent their anger”. This rage of Hindus – which Modi said in his public statements at that time was a justified reaction – was because 58 people, including women and children returning from Ayodhya where they had gone to contribute to the building of a Ram temple, had burned alive in a train compartment in Godhra.

You still chose to speak out. To say and do what you did called upon you to summon the highest courage. You said to the SIT and the Supreme Court that Modi had “expressed the view that the emotions were running very high amongst the Hindus and it was imperative that they be allowed to vent their anger”. This rage of Hindus – which Modi said in his public statements at that time was a justified reaction – was because 58 people, including women and children returning from Ayodhya where they had gone to contribute to the building of a Ram temple, had burned alive in a train compartment in Godhra.

You also charged that chief minister Modi “impressed upon the gathering that for too long the Gujarat Police had been following the principle of balancing the actions of Hindus and Muslims while dealing with the communal riots in Gujarat. This time the situation warranted that the Muslims be taught a lesson to ensure that such incidents do not recur”. Your accusations, if accepted, would have resulted in serious criminal charges against Modi, and would also have come in the way of his rise to the country’s highest political office.

Your colleagues in the SIT – fellow police officers – rejected outright your allegations, dubbing you an unreliable witness and claiming that you were not even present at the meeting. Raju Ramachandran, the Supreme Court’s amicus curiae, significantly did not agree with the conclusions of the SIT dismissing your charges out of hand. Ramachandran was convinced that the question

of whether you were indeed present in the meeting needed to be tested in court because the SIT itself held the evidence of those present in the meeting unreliable, and therefore there was insufficient evidence to outright discount your claims. He felt that your word should have been tested in a court of law. Had his advice been accepted, the history of India may have been different, as also your own destiny.

It is unlikely to be a coincidence that the officer heading the SIT was later to be rewarded — when Modi was prime minister — with the unusual and prestigious posting of a police officer as an ambassador after his retirement. You, on the other hand, face nearly a lifetime in prison.

There was reason enough for India’s most powerful men today to hold a deep grudge against you. But India’s institutions should not have been so feeble to allow what appears to me to be an act of petty vengeance and misuse of state power to unfold the way it has.

When I speak out today in your support, there are some who challenge me, asking how I can defend you when a court has found you guilty of custodial torture leading to the death of a man in custody.

In all my years in the civil service and outside it, I have been a resolute opponent of custodial violence and extra-judicial killings. However – as a report in the Times of India confirms, based on data from the National Crime Records Bureau – 180 custodial deaths took place in Gujarat between 2001 and 2016, but not a single police personnel has been punished for any of these deaths. I cannot then be convinced that the action against you is fair in any way.

Had all or many of these custodial deaths been investigated and many police officers been punished for these murders, I would have supported the action that has been taken against you as just. But not when only you and another officer have been punished for the death of a man nine days after being released from custody 30 years ago.

It will not in any way reduce your trials and suffering inside prison to know that there are many people in India who admire you for your sterling courage in raising the gravest criminal charges against one of the most powerful leaders that independent India has seen, and one known not to forgive. I know, as you do, and as Shweta and your children know, that the battle for justice which lies ahead of you will be very protracted, uncertain, replete with many disappointments and heartbreaks.

But I know also that you have the strength and the resilience to hold out, to endure, to continue to fight, to stay firm with what you believe to be true and just. And I know that one day, one day surely, you will walk free. With Shweta and your children, and with large numbers of our countrywomen and men, I wait for that day.

Harsh Mander is a social worker and writer.

*Opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of UMMnews.